Making Good Compost for Growing Great Food

Why Begin with Compost?

Many of you may have attempted to compost kitchen scraps before but perhaps gave up because the end product was slimy "compost." Others may have better luck by throwing kitchen scraps into a backyard pile, or use a compost "tumbler" or faithfully turn a pile of farm animals' manure and bedding. When we are successful at creating good compost, what we end up with is wonderful "humus," or topsoil. When we add this to our garden, our reward is food that is high in nutrition and flavor.

To be successful in making compost, we can look at how nature does things. New life is constantly being created, but when plants and animals die, nature doesn’t throw them in a landfill. Instead, she "composts" them to help nurture new life. Nothing wasted and everything used.

So many gardens and farm fields today are now without topsoil. Repeated tilling, soil lying bare in the winter, and the use of herbicides and pesticides all result in no living topsoil and crops with depleted nutrition. Our alternative is to copy nature's model of recycling. We have everything necessary: all of us have kitchen scraps, many of us have yard wastes like leaves, branches and dead plants, and those with farm animals have manure and bedding such as straw. Whether you live in the city, suburbs or rural areas, you not only have the makings for compost, but compost is necessary for the wonderful produce that you will be growing.

Basic Ingredients for Composting:

1. Organic material:

This is our main ingredient. Strictly speaking, “organic” means "made of carbon," and we can think of carbon as coming from any living source. Successful composting requires a ratio of about 25 to one; that's 25 brown-carbon to one green-carbon source. “Browns” are brown because they’re dried out or older, like dried leaves and grasses, dead plants, wood branches or hay and straw. “Greens” are fresher items like grass clippings, vegetable and fruit scraps from the kitchen, and manure from the chicken house. If browns don’t exceed greens by a large ratio, sloppy and “yucky” compost results!

2. Air: Almost all living beings need this essential ingredients and so it’s obvious that the millions of microscopic creatures in our compost pile do too. Without air, harmful bacteria (the “anaerobes”) proliferate and we end up with a stinky compost pile. That’s why the commercial “compost tumblers” of all sizes come with screened openings and handles to allow frequent turning of the ingredients. Compost in backyard open bins need to get turned with a fork, though building these piles around empty drainage tiles allows not only air to get in, but also water when necessary. Large compost piles on a farm get turned with a tractor—thank goodness.

3: Water: This essential ingredient allows the necessary chemical reactions to take place during composting by keeping microbes alive and active. Some people build their compost pile around a perforated drainage tile so they can water the pile through the tile during dry times. Others water their pile when they turn it. Compost with lots of "green carbon" items usually have enough water. Your composting material might need water if it appears dry, no longer heats up, or crumbles rather than having the consistency of a damp sponge. Compost that is too wet can be diagnosed by a bad smell because air can’t permeate the compressed material. You will also be able to squeeze water out of composting material when it is too wet.

4: Heat:

Heat is integral to composting because it comes mainly from the chemical reactions taking place during decomposition. Warmer ambient temperatures do speed up composting though, and that’s why compost tumblers are painted dark colors to speed up the composting process. I find it fascinating (because I’m a bit of a science nerd) that there are both “mesophilic” and “thermophilic” bacteria that operate at different temperatures. They simply go dormant when the temperature isn’t optimal for them. Hurrah for successful composting even when we aren’t aware of all the nuances!

5: Microbes and minerals: Essential microbes proliferate in our compost if we don’t use pesticides. These microbes and minerals come from ingredients that include manure, leaves, grass, old garden plants and produce. Adding leaves from deep-rooted plants like comfrey and trees add even more microbes and minerals. Microbes are essential players that consist of bacteria and fungi, as well as nematodes and protozoa. Because we’re dealing with living creatures with microbes, we want to give them a good environment in our compost.

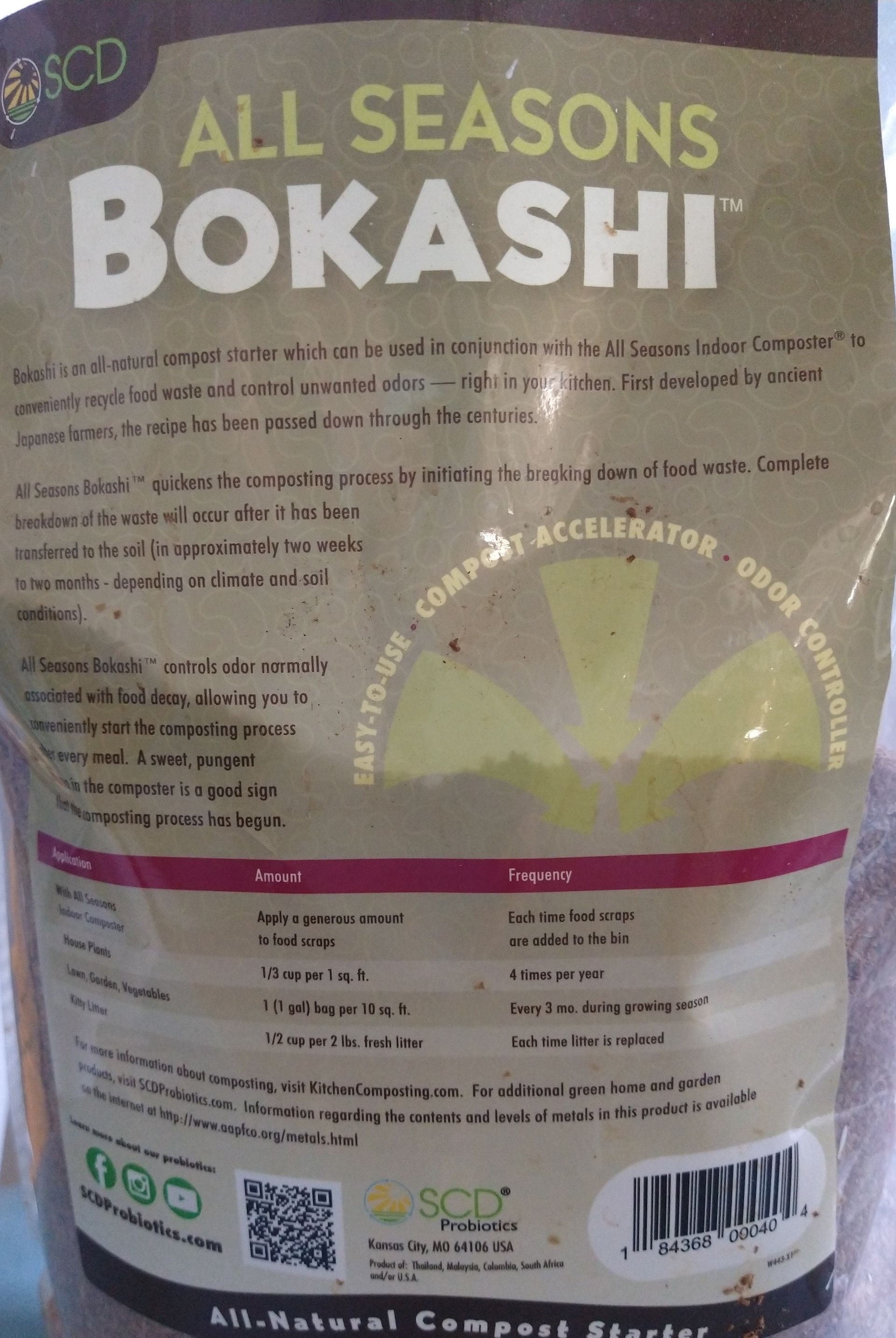

I have recently been using a "Bokashi" mixture of bacteria that I add directly to the compost pail that is kept under the kitchen sink. This has worked so well for rapidly breaking down the kitchen produce even before I carry it out to the compost tumbler. Bokashi is actually a mixture of bacteria that helps to ferment the kitchen scraps instead of actually composting them. The result has been a much quicker way of creating soil that can actually be applied directly to the garden.

Hints for Creating Great Compost:

Manure, the good and the bad:

For those of you who aren’t farmers with livestock and don’t have rabbits or chickens in your backyard, it’s still helpful to find a source of manure to add to your compost. Manure is packed with the microbes that were necessary in the animals' intestines to digest their food. These same microbes are extremely helpful in speeding along the composting process.

I used to encourage people to source manure from a farmer who might have extra. However, during the last decade a surprising number of farmers have begun using products like “Grazon” to kill broad leaf weeds in their pastures. Because these herbicides persists in the manure of these animals, the manure will kill our garden plants too. I’m rolling my eyes as I write this, because after having both horses and cows, I know that not only do broad leaf “weeds” contain many nutrients, but that animals seek them out to add to their grass diets. Even if I don't understand the logic behind farmers using these herbicides, it's best to avoid manure from animals where any herbicides have been used.

If having animals isn’t an option, then we human animals can make some pretty good manure too! When we had interns on our farm, it was fun and convenient to put a compost toilet in the old outhouse. Commercial compost toilets cost from $1,000 to $2,000. I admire folks who make their own from a five-gallon drywall bucket with a recycled toilet seat on top. Dry sawdust or wood chips at the bottom of any style of compost toilet helps to absorb moisture and odors. A sense of humor can even make this fun.

Make composting easy:

You’re not going to feel like focusing on compost every day, so try to make composting as easy as possible by weaving it into your daily routine. I keep a small bucket under the kitchen sink that receives produce like banana peels, tea bags, egg shells, coffee grinds and inedible parts of garden produce. Every few days, when I head outside for another activity, I can carry the bucket out to the compost tumbler, add some sawdust, and give the tumbler a few spins. After rinsing the compost bucket out with a hose, the job's done.

I am spoiled by having a compost tumbler. Without it, I would need to use the garden fork to turn the compost weekly to aerate it. I did that when younger, but although I still use bins for bulky organic produce, a compost tumbler sure works well. Compost tumblers range in size from about 30 gallons to 100 gallons. It's handiest to have them divided inside. Although both sides turn together, one part can age while more items are added to the other side. Additionally, I keep a five-gallon bucket of sawdust from a nearby lumber yard beside the tumbler. This is the “brown” ingredient that I scoop into the tumbler every time I add kitchen produce.

Avoid all chemicals:

I’m afraid that it’s not just farmers who are supporting chemical companies. Herbicides that kill broadleaf plants may be found in grass clippings from roadsides or residential lawns. If you get straw or hay elsewhere, make sure it hasn’t been “dried down” with Roundup or treated with any insecticide or fungicide. To create living soil, we need all the living organisms that are part of the soil-food web.

The smaller ingredients the better:

Nature’s first step in composting is the work of the many creatures that shred large ingredients. Likewise, we can speed up our composting process by shredding leaves with a lawn mower or having the chickens shred kitchen scraps by eating them. What comes out their other end is then ready for the compost pile. At our farm, we discovered that running the cows’ straw bedding and manure through the manure “shredder and spreader” as it goes into the compost pile greatly reduces the time it takes for the pile to turn into beautiful compost.

Avoid wet or smelly compost:

The main reason I’ve seen people give up on composting is that their product was consistently wet, goopy, and smelly. Remember that you need twenty parts “browns” to one part “greens” for good compost. Having plenty of straw, wood chips or dried leaves to balance the wet produce from the kitchen will solve this problem. In the autumn, the dying garden plants also make excellent “brown” ingredients.

If your pile smells bad, it may be too moist, but bad odors can also be caused by the ingredients themselves. If your kitchen scraps go directly into the compost pile, bury them a few inches into the compost so they won’t smell as they decompose. This will also help keep the neighbor dogs away!

Using your beautiful compost:

After a few months, you will have organic material in all stages of decomposing. The younger compost will still have recognizable kitchen scraps, but once aged with air and moisture, the older organic material will have become “humus,” or the organic material worthy of nurturing your plants. Far from “deadened soil” or dirt, this compost can be layered on your garden each spring. It is alive with microbes and insects that will interact with your soil and plants to bring nutrition from the soil to your produce. You can also use compost for potted plants or for “topdressing” plants that are already growing. In addition, we use it extensively in the hoop house to nurture our crops.

Benefits of Compost:

I wish there was a way to measure the nutrient content of food, because compost increases the "nutrient-density" of food as judged by how flavorful the produce grown is when grown with compost. Currently, "BRIX" is used to measure the sugar content of produce which is assumed to parallel the nutritional content. I've used a brix meter, but find it easier to use the "taste test" on our produce. Studies have shown that the higher the nutritional content of food, the move flavor it has. My conclusion is that composting to create topsoil is not only worthwhile, but essential for the taste and nutrition of the food we want on our dinner tables.

Currently, the Bionutrient Food Association is working on creating a meter that we can bring to the grocery store, Farmers' Market or use with our home-grown produce to see how "nutrient-dense" our food is. Even without being able to measure its nutritional content, I believe you'll be pleased how much more effective and sustainable compost and compost tea are than any commercial fertilizer in producing nutritious and delicious food.

Brix meter for testing sugar content of produce indicating its nutritional quality

-

Can I have a compost pile in the city or in a small backyard?

Even a small outdoor space allows you to have a compost pile. Keep the ratio of browns to greens high, like 3:1 so that the pile will not be smelly and will compost well.

-

What's the most important thing to do when making compost

The biggest key to success is to use a lot of brown (high carbon) material to greens (high in nitrogen).

That means that you need to have a lot of leaves or sawdust to balance out your kitchen scraps.

-

Are there things that never should go in a compost pile?

Never put items in that compost slowly, because your compost pile will begin to have a bad smell. That means not putting in meat scraps, bones, grease, whole eggs, or any kind of dairy products like cheese.

City parks have exchanged expanses of green lawn for concentrated growing areas tended by people who laugh and talk together as they work. In some areas there are raised beds densely green with growing fruits and vegetables. The source of their soil is evident as there are many rectangular chicken tractors where busy hens create compost by scratching through leaves, wood chips, and food scraps. They even provide eggs while making raised beds for next summer’s community gardens! We also notice irregularly-shaped hills on which fruit trees and berries are growing. This is called “hugelkultur,” and is a popular way to grow food with less water. Rotting wood, that would otherwise be wasted, is buried to provide heat, water and nutrients for the plants growing above.

Mary Lou

mlgrowinglocalfood@gmail.com